The blinding, belated brilliance of Bob Dylan’s Street-Legal

By NICK TAVARES

STATIC and FEEDBACK Editor

The other night, I was working on something unrelated to anything and unimportant by any measure. But significant or not, this needs music, and after a few quick scrolls, it seemed like Bob Dylan would be a decent pick for right then. One of those scrolls wound up around the “S” albums in his catalog, so, why not, let’s give Street-Legal a shot tonight.

This is not an album I listen to much. I own it, but I can’t remember the last time I actually sat down and went all the way through it. “Changing of the Guards” started things out much brighter and jumpier than I remember, and it grabbed me. It grabbed me like I hadn’t heard it before, as if all memory of this record had been wiped from my memory. And it felt like that because I immediately loved it.

It took all of 30 seconds into “New Pony” before I realized how ridiculous this was getting. This was a tough, nasty blues tune, territory he wouldn’t travel again until his revival at the turn of the century. The guitar riff snarls, the band is tight, even the sax solo is nasty. The only fault in the song comes in its fade-out, depriving the listeners of an awesome jam just before the five-minute mark.

This continues all through the album. Some of this points to the future direction of his work — background singers were soon to be featured players on his tours and albums, and he similarly began putting a higher priority on the dexterity of his guitar players. It’s not that this all sounds modern or advanced, it just sounds like it’s totally out of time and place with most of Dylan’s work of the era. If he could resurrect his mid-70s voice today, this album could almost pop out as-is tomorrow. It’s stunning.

There’s a juxtaposition that that production sets up with the lyrics. “We Better Talk This Over” keeps that biting spirit of “New Pony,” with a story that’s clearly inspired by the end of a relationship. “Where Are You Tonight?” plays like a straight epic, all gospel and righteous rock and roll oblivion to close out the album, but the words paint these vivid scenes, surreal and literal side by side, while the song’s narrator stumbles through stages and streets looking for the one who isn’t there. Like the best of Dylan’s work, it’s crushing and inspiring all at once. It’s a wonder that should be highlighted in every best-of compilation.

The one song that seems to have some consensus is “Señor (Tales of Yankee Power),” another tale of a lost soul at the mercy of a foreign power. This was at least included on his Biograph box set and gets covered by other artists with integrity (including Willie Nelson and Jerry Garcia). That said, listening with fresh ears and emboldened by the rest of the experience, it now feels like a masterpiece. This is a great record. How have I gotten this far without realizing all this?

Because Street-Legal is a bad record —or, so goes the thought. A few contemporary reviews that are still available have some choice words for the album: “overripe,” “turgid,” “wretched.” Those assessments grow legs, and they march on through the years, and at some point I bought a CD, listened a couple of times, ripped it digitally and forgot it in a sea of files.

Bob Dylan is the guy with a guitar and a harmonica, and any and all deviations from that set-up are a cast as a bizarre deviation from the accepted norm. And I must’ve been guilty of that on some subconscious level. Though I was immediately enthralled with the older, worn vocal tics and full-band presentation of Time Out of Mind and Love and Theft, I probably listened to this once or twice in the early 2000s and then moved on; maybe “Señor” remained in the occasional rotation, but nothing beyond that.

So it is and so it remains. This is forever catalogued as a misstep in the discography, Dylan moving outside of his designated realm and delivering a flat collection of songs. Give it a glance on the way to Slow Train Coming, but there’s no need to linger on this record. And there it remained in the collection.

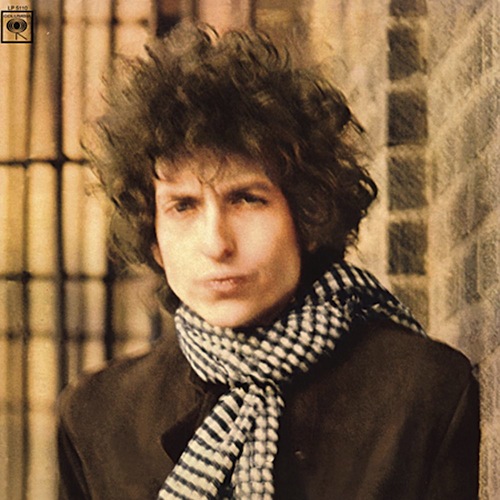

And there’s a shame. For whatever reason, I spent years not enjoying this as, to these ears, one of Dylan’s better-sounding albums, at least sonically. Reaching for that lush, Spector-esque sound led him to a similar destination as Bruce Springsteen on Born to Run, Darkness on the Edge of Town and The River. Even “Changing of the Guards” has a very Clarence Clemons-esque sax refrain. When there’s no one way to deliver a set of songs, or poems set to music, there’s no reason why it can’t be with a lot of people in the room, just as it could be with one man and an acoustic guitar. It’s all a matter of whether or not it’s done well, or at least done with taste. Coming off of the introspectiveness of Blood on the Tracks, then building upon that the wild sounds of the Rolling Thunder Revue, taking that wily sonic palate into Desire, then first testing out the big-band swing of the expanded cast on his 1978 Japanese tour, he lands here. And it’s sharp.

A quick check on his official site shows that, somehow, “New Pony” never went out for a ride on stage. In fact, save for “Señor,” none of the songs from Street-Legal survived the 1978 tours. The one exception here came on the first night his 2000 tour, on March 10 in Anaheim. Out of nowhere, he breaks out “We Better Talk This Over” with altered lyrics to an obviously enthralled assembly of diehard fans. But that’s it. From this point on, this and all non-“Señor” songs from Street-Legal went back in the archive.

Maybe that shows that Dylan and the critics were in agreement on this one. At some point, as the years pass and each new album ceases to be a referendum on an artist’s entire career, the discography is summarized, collected and set in stone. Dylan’s summary runs much longer than most: there are his early folk years, turning electric in the mid-1960s, going into the woods after his motorcycle accident, returning to prominence with Blood On the Tracks, finding religion, weird albums in the 1980s, and finally the Neverending Tour and a return to prominence in the late 1990s and into today.

There’s a lot left out of that abstract, obviously. There’s not much room for his standards albums of the past few years, or his treks with Tom Petty, or the heroics of Oh Mercy circa 1989. And just the same, that blip between the Rolling Thunder Revue and the heavy Christian albums that gave us Street-Legal is missing.

But this is a prolific artist and, more often than not, a great one. There are great moments scattered on his less-than-stellar albums, and there are great albums lost within a mostly incredible catalog. Here, then, is one more I’m happy to have finally discovered. And there might be more that deserve a second or third look tucked away in there as well — maybe it’s time to dust off Under The Red Sky or Empire Burlesque. But that’ll have to wait until I have Street-Legal out of my system.

Feb. 22, 2019

Email Nick Tavares at nick@staticandfeedback.com