Fifty years later, new sounds collide with classic vibes on George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass

By NICK TAVARES

STATIC and FEEDBACK Editor

Drop the needle onto side one, track one — “I’d Have You Anytime.” The familiar opening guitar lick remains, right out of the best R&B recording room, but somehow befitting of this era, when the 1960s gave way to the ’70s and all bets and restrictions were lifted. It’s the iconic opening to George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass, and in turn, Harrison’s true introduction to the world beyond his cramped role within the Beatles.

It’s also a song I’ve listened to hundreds of times, easily, but here, it’s part of All Things Must Pass — 50th Anniversary, overseen by Dhani Harrison and remixed by Paul Hicks. And while not drastically different, it does play differently enough to be noticeable — the guitars are a bit more sparse, the vocals fuller and floating above the mix, the reverb that penetrated so much of the original record conspicuously lessened. Just as the song served to bring Harrison out of the Beatles and onto his own platform, the first track of this ambitious remix project sets the table for what’s to come — new versions of classic tracks, demo takes and alternate material abound to fill in the margins on a classic moment in recorded music. Simply, the album you knew is the same, but not quite the same as it was.

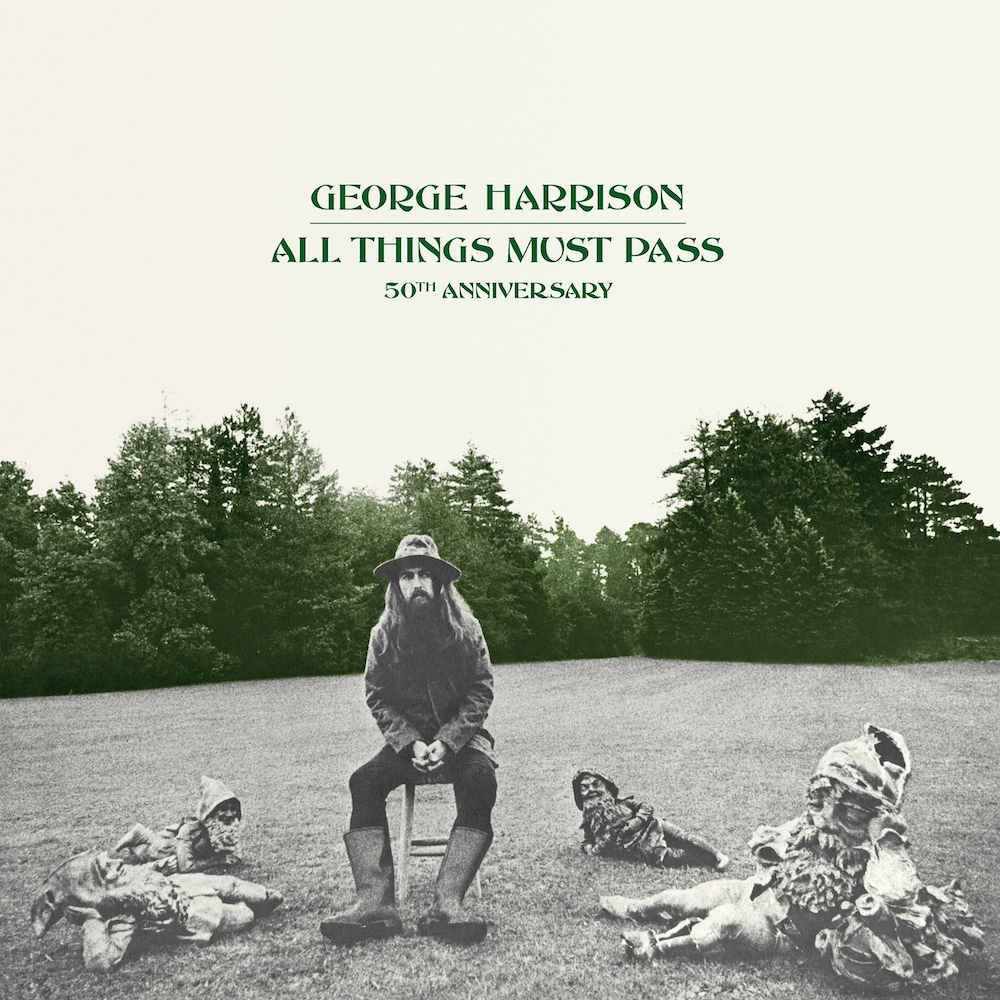

![]()

This new mix makes George Harrison the unquestioned star, rather than Phil Spector's reverb and raft of 10,000 instruments playing at once. Not that this still isn't a dense, layered record, but Harrison's rich tenor is now suddenly front-and-center on every track. Acoustic guitars float up above the din on "If Not For You," with strings adding punctuation to the instrumental calls on "What Is Life" — or are those synths? The notes by Hicks and Dhani Harrison in my edition of this album (I'm holding the five LP version) seem to suggest that some of those organic sounds might not be so.

There are some more shocking revelations to be found, though, once buried within the tracks and now bubbling to the surface. The odd chanting, spoken backing vocals on "The Ballad of Sir Frankie Crisp (Let it Roll)" sent me running to the lyrics to figure out what I was hearing. As it turns out, it was just a repeated call of "Oh, Sir Frankie Crisp." I'm not sure I would've brought that bit back from the depths, but listening along to the Day 1 demo of the song reveals it was there as well. Whether it deserved to remain buried is up to the listener, ultimately. And going back to the original release of the record reveals that, yes, that was present there, too. It was just much more subtle and easier to ignore.

But those questionable decisions amount to less than a handful, and it's nit-picking by definition. The open, airy treatment of "Beware of Darkness" gives it an even more sweeping, regal feeling than the one listeners cherished for more than 50 years. And going back to "Let it Roll," the resurrection of that tune's rhythm section is superb, with the bass thumping and locking in with the drums to offer a counterpoint that brings the entire composition to a new level of maturity — not unlike what a certain rhythm section of Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr used to do on Harrison's Beatle tracks.

Starr was still around, and even with Spector's enigmatic presence, Harrison was in charge here. No longer relegated to waiting to work on his two or four songs per record until the other Beatles were ready, he explored the space of the studio and the limits of his über-talented supporting cast. Songs were demonstrated and deconstructed, shattered and glued back together in myriad formations until the final piece took shape. And to that end, the session takes made available are incredibly illuminating.

This iteration has two LPs worth of them, while there are five-CD and eight-record configurations that give an even fuller picture of how the album came to be, with more material from the sessions and a full sampling of everything demoed by Harrison on the first two days of the sessions. I've surveyed these more robust versions as well, and two days worth of such demos make up discs four and five of the deluxe editions, illustrating just how many songs Harrison had entering the recording process beyond the 17 compositions that made the final cut. The session outtakes and jams that follow reveal the communal process of the recording. Spector may have been running the sessions and implementing his vision of a robust sound image on the proceedings, but it's Harrison and friends who brought the required feeling to the actual music.

And despite the seriousness of the material and the long hours in the studio, Harrison's sense of humor didn't let up. Take the opening lyrics of "Isn’t It A Pity (Take 14)," the first entry of the session outtakes:

Isn't it so shitty

Isn't it a pain?

How we do so many takes

Now we're doing it again

But 13 takes later, "Isn’t It A Pity (Take 27)" shows how far the song had come. It's ethereal and haunting, and yet somehow still an entirely different animal than either of the versions that wound up on the completed album. It's enough to wonder if we could have an entire record of "Isn't It a Pity" in all its variations that would, in itself, be a thrilling listen. It all speaks to the inventiveness of the musicians and the creative curiosity Harrison displayed, and that willingness to reach further out to grab a special performance.

When the takes were through, it was time to cut loose, to the point that the musicians would jam for hours after the day's work was through. Instead of heading to the pub, everyone just plugged in, cut loose and let it rip. It was an important enough part of the process that Harrison insisted on the Apple Jam be included as a third record, creating a three-LP set that was then unprecedented in rock and roll. The Apple Jam section, still occupying sides five and six here as on the original, get the remaster rather than the remix treatment, and that’s for the best. And for more proof of Harrison's sense of humor in action, check out his irreverent take on "Get Back" from the session jams.

And in the spirit of giving, Harrison was well aware of the collection of musical titans he had in the room, and he was more than happy to show off what they could pull out of the blue when the formal sessions ceased for the day. More than just a statement of artistic merit or a venting of pent-up songwriting frustration, All Things Must Pass, it seems, looked like a lot of fun to make. Labor intensive and determined, sure, but listen to “Plug Me In” or the wild guitars and horns on “Out of the Blue” and tell me these guys weren’t having a blast in that room. Again, this is reinforced with more jams packed into the bonus section, like the sleazy "Almost 12 Bar Honky Tonk" jam.

In addition to spotlighting Harrison, stripping away the waves of gloss reveal just how powerful the musicians he assembled had played during the sessions. The original album is notable for its cohesive and signature sound, of course. But here, names like Ringo, Bobby Whitlock, Eric Clapton, Dave Mason, Billy Preston, Bobby Keys, Jim Price, the guys from Badfinger and everyone else are finally allowed to shine outside the simple context of Spector's working state. Harrison eagerly went along and gave his approval to that tactic, but taking away just a bit of those reverberating layers allows for something closer to how a more mature Harrison might have tackled these songs.

But the George Harrison of his latter years, the one who was decades beyond the Beatles and contented in his garden, didn't unleash this album onto the world in the wake of the most consequential breakup in music history. This Harrison was 27, with a backlog of songs and a chip on his shoulder and more than ready to step out of the shadow of his warring former bandmates. The wall of sound is as much a character of this record as any song or player.

![]()

I sat with this set for a few weeks before finally committing my thoughts to this space. At first, I was caught up in how new everything sounded and felt. I went down the rabbit hole of all the alternate takes. After some time, I hit pause, receded and went back to the original record. Then that, too, felt fresh and suddenly comforting. Had I been a fan of the remix work here, or was I just happy to have a shiny, new vinyl copy on the turntable?

Like so many things, it’s a little of both. While the remix does change the sound of the album significantly, it still maintains much of the feel of the original work, and the vibe of an artist wanting to not just try anything, but to show he could and would do everything. Listen to "Awaiting on You All," and it still possess all the chaotic energy of 20 musicians belting out a song at once. The closing "Hear Me Lord" takes its opening verses down to mostly Harrison's solo voice before the makeshift choir assembled at Apple Records can join in. And its title track, one that might be the signature song of an incredibly significant artist, keeps its sweeping, elegiac charm through and through. The choral vocals are highlighted a bit more, the horns are less clouded, the guitars punching through the mix strategically, with Harrison's own voice above all, as it should be. Different, but still somehow accurate.

But unlike the recent Beatles remix projects, for sake of comparison, the aim here seems to be to go farther than just bringing new clarity to the music. Those projects — the recent anniversary editions of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, The White Album and Abbey Road — have made use of technology and taken creative liberties, but at the core, the albums and songs remain the same. Here, with different remix producers and engineers, the record sounds and feels noticeably different, almost to the point that the main songs feel like alternate takes of themselves.

To that end, this 50th Anniversary version doesn’t replace the original, or even the 2001 reissued edition. It’s another chapter in the record’s history, and a valuable addition to the shelf. All these tweaks are just that — they're little curves and detours to reveal more of the artist as a young man, to demonstrate just how much Harrison had going on in those fervent first few months of freedom. It stands not to supplant the original All Things Must Pass but to augment it. And importantly, it carries on the legacy of an immensely important record and provides those of us on the outside a greater window into its creation.

The original record is still there, and like the first edition, this version is certainly worth of the hours of listening it will command. Take the time, drop the needle on the first track, and judge for yourself.

E-mail Nick Tavares at nick@staticandfeedback.com