The moon, the stars, the unseasonable cold and Let It Be

By NICK TAVARES

STATIC and FEEDBACK Editor

This is not spring.

Every morning this week has seen a temperature closer to 20 than 30 on the thermometer, with a vicious winter/spring cold that’s left my throat throbbing and leaking and costing hours of sleep every night.

So with that comes the inevitable attempts to pretend that this isn’t happening, that the worst winter in the region’s recent history isn’t spilling over into the next season. Call up some friends, draw up a night out, and so it goes, hanging out in a bar with some impressive people watching while a pretty impressive Beatles cover band (note-perfect but not so committed that they dress up and wear bad wigs) dialing up a dance party for anyone with $12, some just over 21 and many much more so than that. For a couple of hours, with a pint of Sam Adams and space securely away from the dance floor, I could relax for a minute and listen to “Day Tripper,” “We Can Work it Out” and “Ticket to Ride” much louder than I could at home.

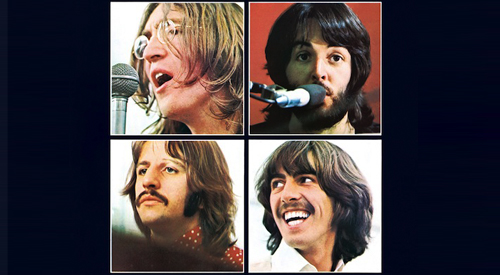

And then they launched into “Get Back,” and I remembered how I used to spend the more seasonable nights in spring when I was well under 21, alone in the dark of my room, self-sequestered and staring out into the sky through open windows while Let It Be ran through on my little boombox, “Two of Us” through to “Get Back” and Ringo’s plea that he hoped they passed the audition, and back again.

Even on the good nights, the Beatles offered an escape.

![]()

In my senior year of high school, I had a project in a writing class to create a moon journal, one page per night of the moon’s month-long cycle. It was pretty open-ended — there could be drawings of the sky, poems, straight meteorological-style renderings, anything. I usually took the path of using the top half of every page to sketch out the moon in the sky in pencil, any stars I could see, maybe the clouds, tops of trees, and below, some kind of description of what was going on, how it looked, along with anything else that might come to mind.

I didn’t take to this easily, though. Most nights in Southern New England in the spring were, of course, cloudy, which rendered the moon invisible more often than not. I kept bringing in blank pages saying, “well, there wasn’t a moon again,” before my teacher pleaded with me to just write about anything, everything, that was happening while the moon wasn’t out.

![]()

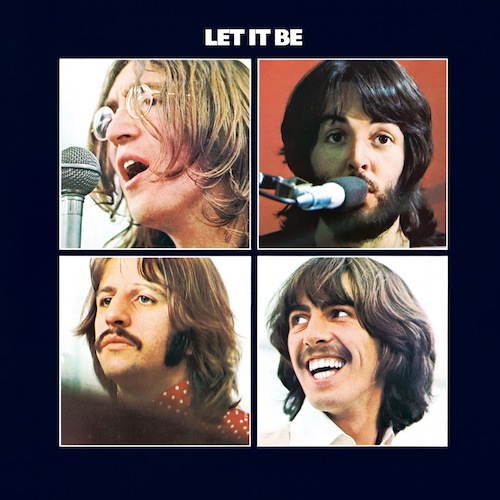

Around this time, I was well into a deep fascination with the Beatles, and to a point in high school where I certainly wasn’t alone anymore in that regard — just because they were old didn’t mean that they couldn’t be cool. Their early hits grabbed me as a kid, but by now, it was the late period — Abbey Road and Let It Be, especially — that kept me enthralled. I noticed backseat critics and the quickly dismissive knocking down Let It Be as the “worst” Beatles album, and that never made any sense to me. Even then, I recognized it wasn’t their best — Abbey Road and Rubber Soul were my kings, then and now — but the spirit on Let It Be is so infectious. There are romantic notions on there, rollicking numbers, tender moments and a casual, confident musicianship that brings it all together.

Because some of my friends who professed to liking the Beatles dismissed it, it started to feel like exclusively mine. As the weather warmed up, I started something of a ritual, opening my windows and blinds as wide as the hinges would allow, kicking back on a folding chair I kept in my room, with my feet propped up and my head and hair dangling over the back, and I’d put on Let It Be and let it play on repeat for as long as I could get away with it.

Certainly not exclusive to me at that age was feeling awkward or left out, and the initial burst of John Lennon’s “I dig a pigmy!” speech to start the album before the joyful “Two of Us” was a welcoming chant. It showed, through the speakers, a group of guys getting a genuine kick out of their job and happy to be doing it. It brought the listener into a magical world. It belied the reality of the band’s situation.

The history of the album, famously, is that it’s the document of a band breaking up. Personalities had grown and tensions had been rubbed raw over seven years of constant work and fame and expectations, leading everything to burst during this album’s recording. That much is captured in the accompanying film, with petty arguments and non-cohesive playing brought to the forefront. But on the album, there was still more than enough to pull it all together, and the result displayed the band at its varied best.

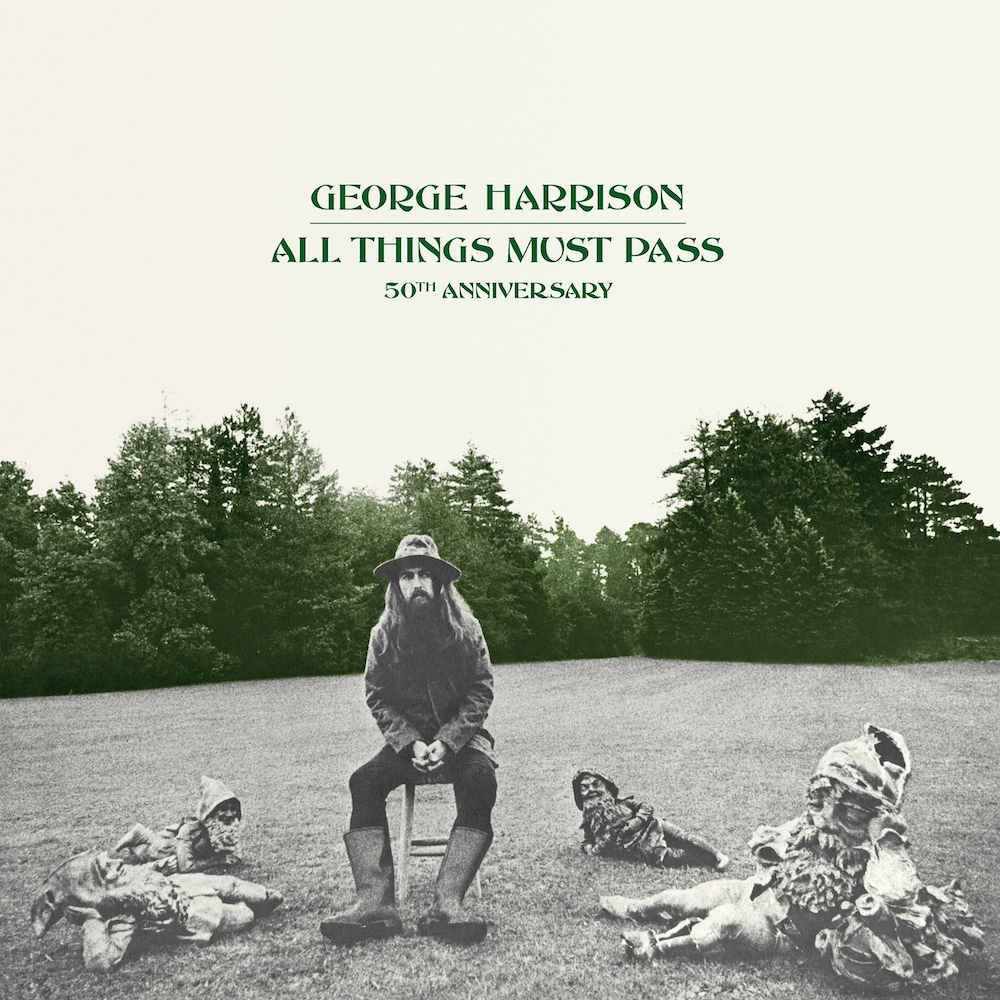

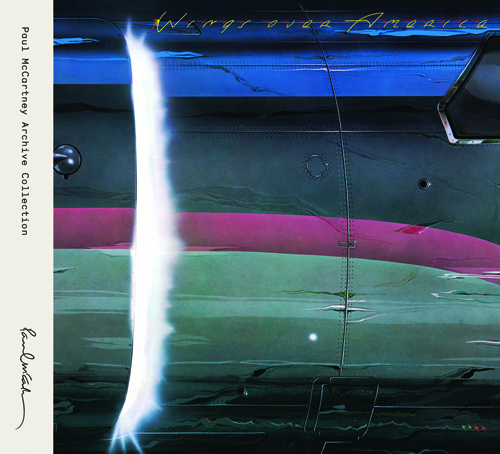

To list the highlights would be to go through each of the dozen tracks, including the “Maggie Mae” and “Dig It” interludes, and to sing their praises. With the lights out and the natural glow of the night beaming in, I could get away from whatever stressful and ultimately stupid thing was bothering me that day and lose myself in “The Long and Winding Road,” or take the simple, sound advise on “Let it Be,” punctuated by George Harrison’s biting solo. I could sit back and laugh along with “Get Back” or paint the fictional garage band in my head while Paul McCartney belted out “I’ve Got a Feeling.”

It was on one of these nights, while Lennon sang “Across the Universe,” that I could finally see the moon peeking out through the clouds. I got the journal — 30 half pages of card stock bound together by binder rings — and started to let go of the frustrations and at least try to put something a little beyond the minimum into this assignment.

![]()

That moon project became just another one in a long line of B+ efforts then, something that I could have really grabbed and controlled, but it was easier to do just well enough to show some kind of promise without giving myself away as someone who actually wanted to express myself and do the best work I could.

If I had it to do over, I’d properly recall those nights, with clear, black skies speckled with stars and only occasionally obscured by stretched clouds in the distance. I used to sit in a folding chair in the corner of my room so that I could see through both windows at once, both open wide with the blinds pulled and the lights out, with my head tilted back and my eyes only occasionally opened.

The wind wouldn’t be blowing but just sort of breezing enough to be felt, not enough to hit with a chill. And my CD player sitting above my bed would be spinning, and right about when it rolled to the third song, “Across the Universe,” I could relax for a minute, forget every idiotic pressure on my 17-year-old head, think about what could come and what I might see and who else might be trying to escape their boring reality on this kind of stark perfect night with John Lennon even more at peace, singing that his world will never change, his life is his own. The notes swirl around in that thin, crisp air, flow out through the screen and start to dance around the trees before extending up through the black and the streaming mist and up with the stars.

The mornings aren’t there, and the nights don’t feel quite that way yet. That’s what I’m waiting for. That’s my spring.

March 25, 2015

Email Nick Tavares at nick@staticandfeedback.com