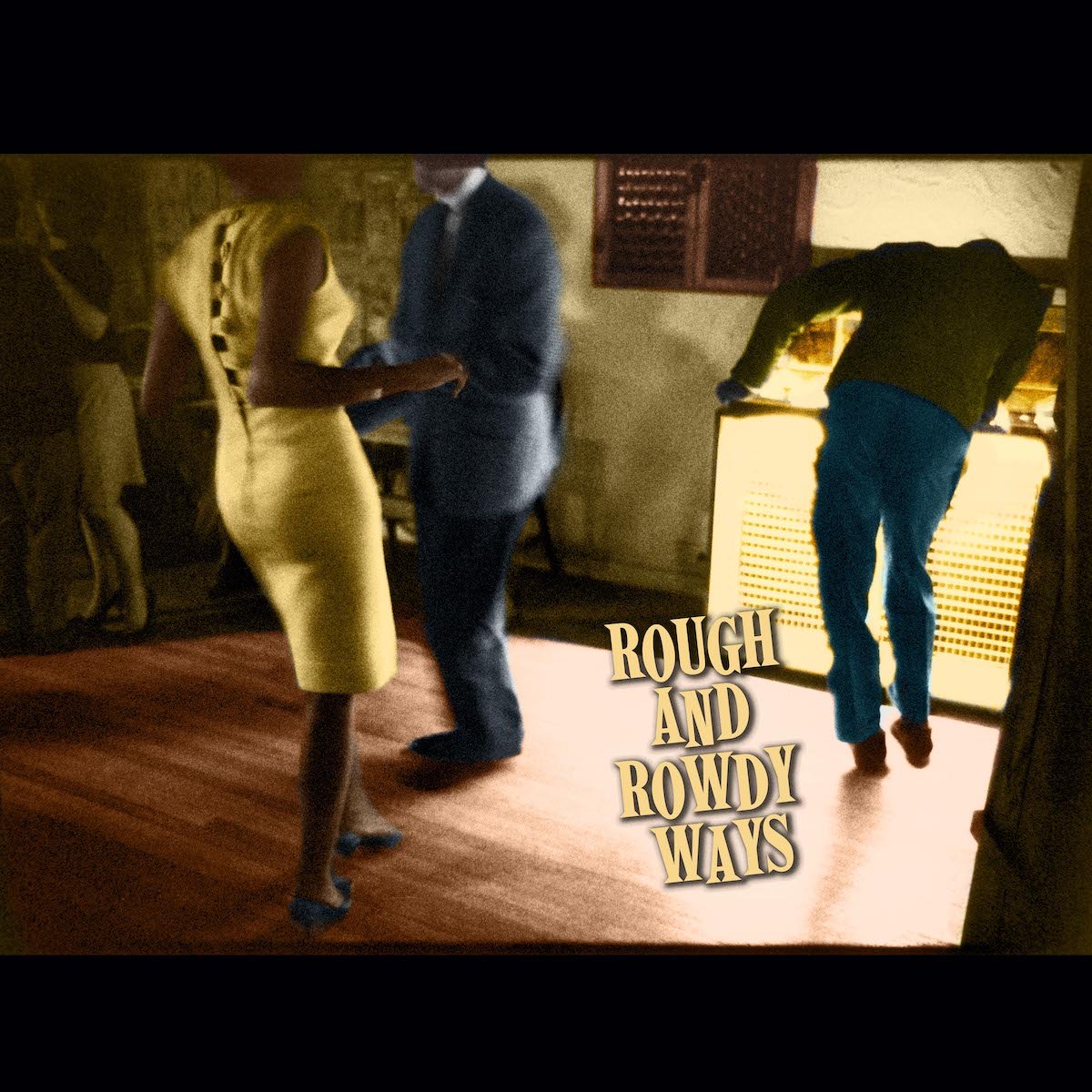

Murder, mystery and melancholy weave together on Bob Dylan’s brilliant Rough and Rowdy Ways

By NICK TAVARES

STATIC and FEEDBACK Editor

The best art typically isn’t over-explained. It doesn’t come with a manual, a mission statement, a “here is what this is specifically about” attached on a tag. At least, the art that most affects me doesn’t usually have that.

So arrived “Murder Most Foul,” a song that would take up an entire side of vinyl, alternating between grisly and poetic details of President John F. Kennedy’s assassination with a who’s who of musical icons, both present at the time and unfolding as the decades move past that moment. That song, the final one on Bob Dylan’s Rough and Rowdy Ways, stands alone on its own disc, yet serves as a valuable prism for the rest of the album.

In what has long been something of a tradition, Dylan’s songs here don’t make specific reference to the political climate or civil unrest that has been bursting for the past four years. Just as he refused to comment on any given moment on anyone’s terms but his own from the 1960s onward, he weaves his way through music and moods, offering observations without advice. Instead of putting forth instructions, he simply lists thoughts and ideas, letting the listener take them as they may.

And there is no shortage of material to digest here. In “False Prophet,” he could be singing in defense of himself or in character, either sincere or sincerely cynical, speaking as the the glut of grifters that have been infecting society for as long as there has been the opportunity to infect, or perhaps as himself and yet another reminder that he is not the voice of anyone but himself. “I ain’t no false prophet / I just know what I know,” is about as direct and indirect as one line can be.

Cloaking everything in an early 20th century aura gives it a timeless feel and places it in sequence with Dylan’s musical approach for the past 20 years, and in stark contrast to everything else in the 21st century. It’s as if he’s a disembodied spirit here, floating above and offering riddles in the place of commentary of the current moment. Where the news is full of outrage and injustice and anger, Dylan sidesteps all of it and offer anecdotes and one-liners from another time. That it all seems to apply so well is evidence of the man’s peerless approach.

On “Mother of Muses,” he takes that idea of moving forward with the help of old inspirations to one of the record’s highest moments. He references old generals paving the way for Elvis Presley and Martin Luther King, longing for bygone days while lamenting how tired he’s become of “chasing lies.” It’s a quiet lament, calling for those spirits to help him carry on, and for new ones to carry forward when he’s gone.

He’s in strong voice here. It’s weary, for sure, but confident and only deploying the rasp that has defined his latter-day work in spots for effect. The past decade of crooning American classics on record and in concert every night has trained his voice into a new animal, like a dark Bing Crosby, offering bits of wisdom and opinion as the album unfolds. There’s so much material to digest in the 10 songs here — I’ve offered examples, but it’s best to let the rest speak for themselves.

Which brings us back to “Murder Most Foul.” Early on in the nationwide lockdown, Dylan released the single to fans, without prior announcement and with no mention of a coming album. And within it, he weaves the news of Kennedy’s death with personal reflection, conspiracy theories, disinterest, anger, acceptance and the constant reminders of the president’s death through the most ordinary of events.

The release of this song went beyond Dylan simply wanting to offer a carrot to fans stuck at home. It doesn’t take much of a leap to regard this moment in time as one that will never be forgotten, and one that could fundamentally change how society behaves. At the very least, no one who makes it through to the other side of this crisis will ever forget its impact. The details will be burned into our collective psyche and we’ll trade stories of what we did, who didn’t make it and how we got through.

So too does Dylan, in regards to the way American life changed on Nov. 22, 1963. He moves past the tragedy and carries on with his life, he listens to theories legitimate and conspiratorial, he listens to the radio and requests songs to ease the load, he goes to the movies to escape for two hours at a time. Time marches on without the 36th president of the United States, but with the clock stopped and restarted from then on.

It’s as if every event in his life is just broadcast through the prism of Kennedy’s assassination, every event just a distraction from that event and the one waiting for us all. Whether he’s heading to Woodstock or Altamont or listening to the radio, or just enjoying someone else’s company in a quiet moment, every verse is interrupted by this horrific reminder of what has happened and how it happened and how it’s not going to stop. It’s biblical in the way the distractions are systematically disposed of and reality creeps back into its place.

The way the song was released speaks to his role as a detached narrator of the current time. The song, at nearly 17 minutes, arrived without warning on a Friday morning and with a simple message to listeners:

Greetings to my fans and followers with gratitude for all your support and loyalty across the years.

This is an unreleased song we recorded a while back that you might find interesting.

Stay safe, stay observant and may God be with you.

Bob Dylan

That note — that it was a song “you might find interesting,” as if he was unaware that his every move is followed and dissected like those of few others — says more about Dylan’s approach than most of the interviews he’s given through the years. But how it was released won’t make as much of an impact as the song itself will through the years. What makes the song, and the record on the whole, work so well is that it’s not meant to be a definitive take on history or the current era. It’s a glimpse from a point-of-view, one not necessarily expert, but well-read and leaning on experience.

Throughout his career, he’s tried to reflect his personal truth and add some perspective to history as it unfolds, whether it’s direct or opaque. He leans towards the latter here, but in such a confusing time, that makes the message all the more relevant, whatever it might be.

E-mail Nick Tavares at nick@staticandfeedback.com